Finally, We Can Define Introversion by What It Is vs. What It Is Not

Too often, in Western culture especially, we define introversion as the absence or lack of extroversion—instead of as a core personal trait in its own right.

Do you, as someone who tends toward introversion, refer to yourself as not extroverted?

Do you run around saying “I’m not an extrovert”?

Of course not (or at least I hope not!).

You probably just say you’re introverted or an introvert instead.

Or maybe you keep things precise by saying something like, well, “I tend toward introversion.”

Great!

Note, though, how you do not say “I tend toward lack of extroversion.”

Do you describe yourself as not warm, not gregarious, not assertive, not active, not positive, not [fill-in-other-extroverted-trait(s)-here]?

Once again—of course not.

You don’t describe yourself as, or define yourself by, what you’re not.

You focus on what you are.

Seeking a Way to Define Introversion

Why is it, then, that in both everyday life and—much more so—in academic research, introversion is so frequently seen … and referred to … and studied not as its own entity with its own positive aspects and descriptors, but rather as—to coin a term—non-extroversion?

Why not look at … and refer to … and study introversion as introversion instead?

And why not identify the key traits that characterize introversion, instead of saying introversion is simply the opposite of, or lack of, the ones that characterize extroversion?

It’s all a bit strange, isn’t it?

That’s what researchers Dane Blevins, Madelynn Stackhouse, and Shelley Dionne point out in an eye-opening—and empowering—article in the International Journal of Management Reviews.

“Righting the Balance: Understanding Introverts (and Extraverts) in the Workplace” is groundbreaking if only for one reason.

For the first time—particularly in the realm of research—it attempts to define introversion by what it is vs. what it is not.

The Concept of Facets

Extraversion is one of the so-called Big 5 personality traits, along with openness to experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and neuroticism. (Note: For the fascinating scientific backstory on how the Big 5 were identified, see my blog post entitled “There’s a Reason Your Introversion Is So Influential in Your Life.“)

Everyone’s personality, the thinking goes, is made up of some combination of these five broad traits. (I’m oversimplifying here, but you get the general idea.)

Each of the Big 5 traits, in turn, is composed of six traits of their own called facets.

The facets of extroversion are:

- Warmth/friendliness

- Gregariousness

- Assertiveness

- Activity level

- Excitement seeking

- Cheerfulness/positive emotion

What are the facets of introversion (extroversion’s counterpart on the extroversion-introversion spectrum), you might ask?

None have ever been spelled out—none besides, I suppose, unwarmth or low warmth, ungregariousness or low gregariousness, and so on.

So in their article, Blevins et al. offer their proposals on the matter.

Using Facets to Define Introversion

The researchers did not pull their ideas out of the sky.

They analyzed 69 academic articles (from psychological and management journals), all of which featured explicit hypotheses about the role of extroversion and/or introversion in the phenomenon(a) being investigated.

Here are the three proposed facets of introversion the researchers came up with:

Introspective thoughtfulness (characterized by the adjectives or action statements reflective, observant, sense-making, deep thinking, and analytical).

Independent mindset (works independently, autonomous, self-sufficient, self-reliant, enhanced sensory processing).

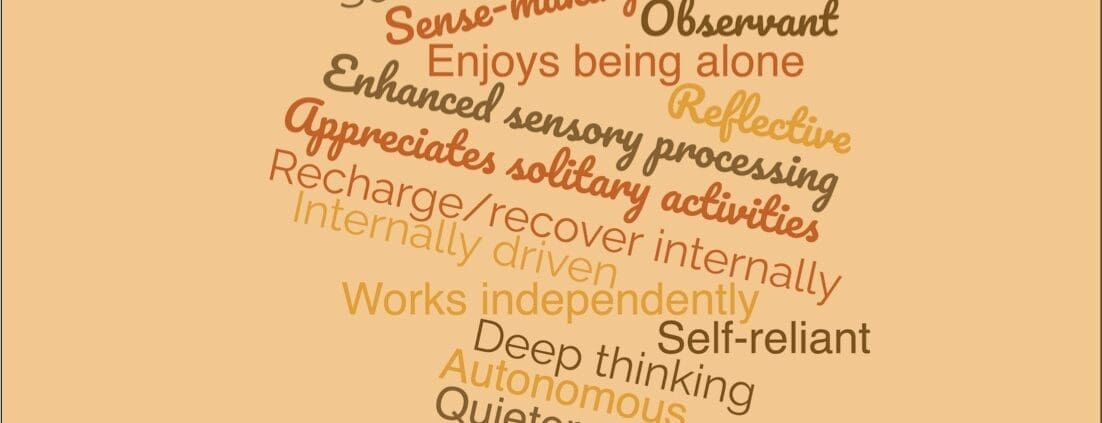

Solitude preference (internally driven, enjoys being alone, recharge/recover internally, appreciates solitary activities, quieter).

As Blevins et al. conclude in their article:

“We suggest, by conceptualizing introverted individuals with more positively valenced characteristics (such as being reflective, independent, and analytical), that research can more clearly capture the benefits tied to introversion.”

The researchers stress that the facets they’ve identified comprise a “working list of adjectives and traits [of introversion] that future scholars may wish to revisit and refine.”

Fair enough.

But now scholars—and the rest of us—at least have some way to define introversion besides not _____ .

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!